Anesthesia area and hole location

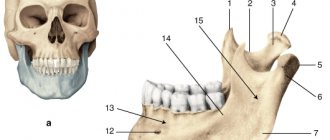

Incisors, canines and premolars on one side (31, 32, 33, 34, 35 or 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 teeth), their gums on the vestibular side and the alveolar process. According to Weisblat's data, the foramen mentalis (the desired hole) differs in location in children, adults and the elderly. In mature people, it is located between the first and second premolars or under the second premolar (somewhere in the center of the height of the body of the lower jaw). In children it is somewhat shifted forward, and in old people in the absence of teeth (which happens quite often) it moves downwards, closer to the alveolar edge.

Conduction anesthesia of the upper extremities using subclavian access

Key words: conduction anesthesia, subclavian access

In recent years, methods of regional anesthesia have been widely used in various fields of surgery. This is due both to the introduction of modern medical technology and to the synthesis of safe local anesthetics, which is especially important for operations on the upper extremities, which are characterized by longer duration and more trauma. The use of regional anesthesia during these operations allows one to avoid complications of general anesthesia, especially in patients with a high degree of risk (concomitant cardiac pathology, diabetes, etc.), allows for early postoperative activation of the patient and does not require large material costs [2-4].

Material and methods. We used the technique of conduction anesthesia of the upper extremities using a subclavian approach during traumatological, orthopedic and microsurgical operations: fractures of the forearm bones with traumatic damage to tendons and blood vessels (12 patients, 37%), condition after metal osteosynthesis (10 patients, 31%), application of an arteriovenous shunt for program hemodialysis (5 patients, 15%), post-traumatic compressive neuropathy (3 patients, 9%) and others (2 patients, 8%).

32 patients aged from 18 to 70 years were operated on, of whom 18 were men, 14 were women. 12 patients had concomitant diseases (coronary artery disease, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus).

The anesthesia technique consisted of premedication with atropine 0.3-0.5 mg, dormicum 2.5-5 mg and fentanyl 50 µg intravenously on the operating table. Then, through the subclavian approach, a puncture of the brachial plexus was performed using PAJUNK (Geisingen/Germany). After receiving a response—contraction of the muscles of the fingers—bupivacaine 0.5% in an amount of 30 ml was administered using the GAMID [1,2,4]. The block usually occurred after 30 minutes and lasted up to 3.5-4 hours, intraoperative monitoring was carried out using the Infinity Vista , system blood pressure, blood pressure diast., blood pressure average, Sp02, heart rate, ECG were determined.

Results and discussion. The effectiveness of the brachial plexus block was adequate.

In 3 patients, due to insufficient mosaic anesthesia, the operation was continued under multicomponent intravenous anesthesia. After the end of the operation, patients were transferred to the ward with stable hemodynamic parameters. There were no complications associated with conduction anesthesia using the subclavian approach.

Conclusion. Conducting conduction anesthesia using a subclavian approach during operations on the upper extremities is a safe method that avoids complications of general anesthesia.

Literature

- Mulroy M. Local anesthesia. Illustrated practical guide Ed., 2nd, 2005, 301 p.

- Ostrovsky N.V., Taraskin A.F., Polyaev V.O., Popov A.Yu. Conduction anesthesia of the extremities. 2007, 48 p.

- James P. Ramphele, Joseph M. Neal, Christopher M. Viscuomi. Regional anesthesia. The most essential things in anesthesiology. 2007, 272 p.

- Mayer G., Büttner J. Peripheral regional anesthesia. 2010, 260 p.

Technique

With the intraoral method of submental anesthesia (sometimes it is also called that), the patient keeps his mouth either completely closed or slightly opens it. The doctor moves the lip and cheek as far as possible, and makes an injection to a depth of 8-10 mm down, forward and inward (this is how the mental canal “goes”) into the transitional fold above the middle of 46 or 36 (first molars) at an angle of 45 degrees. The tip penetrates the area above 47 or 37 (second molar). The doctor releases a “test” dose of 0.5 ml and waits for the patient’s reaction. When tingling and pain appear in the nearest area (for example, the lower lip), then the doctor consciously “falls” 3 mm into the canal and injects another 1 ml of the substance.

The extraoral method of mental anesthesia in dentistry implies that the patient’s mouth is closed, while the chin hole is identified and pressed on it using the free left hand (with the thumb when performed on the right side or the index finger on the left). The needle goes down and forward slightly above the hole. As soon as it touches the bone, they follow the same pattern: release a little, wait for a reaction, “fall” into the canal, release the main part.

Mental anesthesia. Methodology, zone of anesthesia, complications.

Mental anesthesia (mental anesthesia) Anesthesia in the area of the mental nerve.

To perform mental anesthesia

it is necessary to determine the location of the mental foramen. More often it is located at the level of the middle of the alveolus of the lower second small molar or the interalveolar septum between the second and first small molars and 12-13 mm above the base of the body of the lower jaw. The projection of the hole is thus located in the middle of the distance between the anterior edge of the masticatory muscle and the middle of the lower jaw. The mental foramen (the mouth of the mandibular canal) opens posteriorly, upward and outward. This should be remembered in order to give the needle a direction that allows it to be inserted into the canal (Fig. 5.25, a).

Extraoral method. When performing mental anesthesia on the right half of the lower jaw, a comfortable position for the doctor is to the right and behind the patient. “Switching off” the mental nerve on the left, the doctor is positioned to the right and anterior to the patient. Determine the projection of the mental foramen onto the skin and use the index finger of the left hand to press the soft tissue to the bone at this point. Having given the needle a direction taking into account the course of the canal, the needle is inserted 0.5 cm above and posterior to the projection of the mental foramen onto the skin (Fig. 5.25, b). Then it is moved down, inward and anteriorly until it comes into contact with the bone. By injecting 0.5 ml of anesthetic and carefully moving the needle, they find the mental opening and enter the canal. The feeling of a characteristic sinking of the needle can serve as a guide. The needle is advanced in the canal to a depth of 3-5 mm and 1-2 ml of anesthetic solution is injected. Anesthesia occurs within 5 minutes. If the needle is not inserted into the canal of the lower jaw, then the anesthesia zone, as a rule, is limited only to the soft tissues of the chin and lower lip. In this case, anesthesia in the area of small molars, canines, incisors and alveolar parts is not sufficiently expressed.

Intraoral method. With the patient's jaws closed or semi-closed, the soft tissues of the cheek are moved to the side. The needle is inserted a few millimeters outward from the transitional fold, at the level of the middle of the crown of the first large molar (Fig. 5.25, c). The needle is advanced to a depth of 0.75-1.0 cm downwards, anteriorly and inward to the mental foramen. Subsequent moments of anesthesia do not differ from those with the extraoral method.

The area of pain relief during mental anesthesia: soft tissues of the chin and lower lip, small molars, canines and incisors, bone tissue of the alveolar part, its mucous membrane on the vestibular side within these teeth. Sometimes the anesthesia zone extends to the level of the second molar. Severe anesthesia usually occurs only within the small molars and canine teeth. The effectiveness of pain relief in the incisor area is low due to the presence of anastomoses on the opposite side.

Complications during mental anesthesia. If the vessels are damaged, hemorrhage into the tissue and the formation of a hematoma, as well as the appearance of ischemic areas on the skin of the chin and lower lip, are possible. If the nerve trunk is injured, neuritis of the mental nerve may develop. Treatment and prevention of these complications do not differ from those for anesthesia of other nerves.

17. Torusal anesthesia. Methodology, anesthesia zone, complications .

Thorusal anesthesia (pain relief in the area of the mandibular ridge according to Weisbrem)

With torusal anesthesia

an anesthetic solution is injected into the area of the mandibular ridge (torus mandibularis).

It is located at the junction of the bone ridges coming from the coronoid and condylar processes, above and anterior to the bony tongue of the lower jaw. Below and medially from the cushion are the inferior alveolar, lingual and buccal nerves, surrounded by loose tissue (Fig. 5.22, a). When an anesthetic is injected into a given area, these nerves can be “switched off” at the same time. During torusal anesthesia,

the patient's mouth should be open as wide as possible. The needle is inserted perpendicular to the mucous membrane of the cheek, directing the syringe from the opposite side, where it is located at the level of the large molars. The injection site is the point formed by the intersection of a horizontal line drawn 0.5 cm below the chewing surface of the upper third molar and the groove formed by the lateral slope of the pterygomandibular fold and the cheek (Fig. 5.22, b). The needle is advanced to the bone (to a depth of 0.25 to 2 cm). 1.5-2.0 ml of anesthetic is injected, blocking the inferior alveolar and buccal nerves. Having moved the needle a few millimeters in the opposite direction, 0.5-1.0 ml of anesthetic is injected to “turn off” the lingual nerve. Anesthesia occurs within 5 minutes.

Zone of anesthesia during torusal anesthesia: the same tissues as during anesthesia at the opening of the lower jaw, as well as tissues innervated by the buccal nerve: mucous membrane and skin of the cheek, mucous membrane of the alveolar part of the lower jaw from the middle of the second small molar to the middle of the second large molar tooth Due to the peculiarities of the relationship of the buccal nerve with the inferior alveolar and lingual nerves, anesthesia in the area of innervation of the buccal nerve does not always occur. In this case, additional infiltration anesthesia should be administered in the area of the surgical field to “switch off” the peripheral endings of the buccal nerve.

Complications

- Neuritis of the mental nerve occurs if the needle goes too deep into the mental foramen and injures the nerve fibers. Treatment is carried out by a team of “dentist + neurologist”. Prevention - place a stopper on the needle and measure the distance correctly

- ischemia in the chin area and lower lip area. Most often goes away on its own after the anesthetic wears off.

- hematomas can occur when blood vessels are injured and the needle is advanced too quickly when performing mental anesthesia. As always, the anesthetic should be released slowly so that the vessels have time to move under the force of diffusion. It is believed that pain relief performed in less than a minute cannot be considered high-quality

This time there are 2 videos at once (both not in Russian). Watch the first from 1:00, the second in its entirety (there are no audible comments at all, only English subtitles).

There are extraoral and intraoral methods of mental anesthesia.

Extraoral method Anesthesia technique When working on the right half of the lower jaw, it is more convenient for the doctor to stand to the right and behind the patient. When working on the left, the doctor is positioned to the right and in front of the patient. Using the above anatomical landmarks, the projection of the mental foramen onto the skin is determined. The index finger of the left hand presses the soft tissue to the bone at this point. Having given the needle a direction taking into account the course of the canal, the needle is inserted 0.5 cm above and posterior to the projection of the mental foramen on the skin. The needle is advanced downward, inward, and anteriorly until it contacts the bone. Inject 0.5 ml of anesthetic solution, carefully moving the needle, find the mental foramen and enter the canal, which confirms the feeling of the characteristic sinking of the needle. The needle is advanced into the canal to a depth of 3-5 mm and 1-2 ml of anesthetic is injected.

Mental anesthesia

Technique of pterygopalatine anesthesia

Palatal (palatal) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. This path was proposed and applied to the patient Carrea (Cagrea) in 1921 and, independently of him, was developed and introduced into medical practice by us in 1924.

We discovered this path on our own in the following way. When performing a conductive anesthetic injection to anesthetize the anterior palatine nerve—palatal (palatal) conduction anesthesia—we often ended up in the greater palatine foramen. At the same time, we noticed that often an injection from the side of the buccal mucous membrane of the alveolar process is less painful after deepening the needle into this hole by 0.5-1 cm. We began to remove the upper molars using one conductive anesthetic injection at the greater palatine foramen without

' The idea of the possibility of bringing the end of the needle and an anesthetic solution to the maxillary nerve through the pterygopalatine canal was expressed by Voino-Yasenetsky back in 1915, in his dissertation “Regional anesthesia.” However, this author did not test this route on the patient, considering it unacceptable due to the impossibility of insert the tip of the needle into the round hole.

additional anesthesia on the buccal side of the specified area of the upper jaw and observed complete painlessness of the intervention.

We explained the simultaneous anesthesia of the alveolar process, three upper molars and the mucous membrane on the buccal side during anesthesia of the palatal mucosa with anesthesia at the greater palatine foramen (palatal conduction anesthesia) by the fact that if the needle enters deep into the greater palatine foramen (by 5-10 mm) The area of the posterior superior alveolar openings on the tubercle of the upper jaw is washed with an anesthetic solution. Thus, the conduction of the posterior superior alveolar nerves entering the indicated openings, which, as is known, innervate all three upper molars, the alveolar process, the periosteum and the mucous membrane on the buccal side within the said molars, is interrupted.

The anesthetic injection at the greater palatine foramen attracted our attention more and more. We began to insert the needle deeper and deeper into the indicated hole and at the same time noticed that as the needle deepened by 1.5-2 cm, the anesthesia often spread even further forward. We explained this phenomenon by the possibility that the middle superior alveolar nerves arise not from the infraorbital groove, but from the infraorbital nerve behind the inferotemporal surface of the maxilla, similar to the posterior superior alveolar nerves.

Early in 1924, we made a deep anesthetic injection into the greater palatine foramen to remove the roots of the upper right second and third molars in a middle-aged woman. We then used an ordinary needle 3 cm long for this anesthesia; since a certain distance is occupied by the soft tissues covering the palate, and we always leave part of the needle outside, it could only enter the canal 2 cm. But when, after this injection, we experienced pain in the area of the right upper jaw with a probe, we were surprised to find that the entire upper jaw is anesthetized. We removed the roots completely painlessly, without additional anesthetic injections from the outside.

In the process of studying this area, it became quite clear to us that the anesthetic solution, when injected deeply into the greater palatine foramen, is brought quite close to the pterygopalatine fossa, from there it seeps to the trunk of the maxillary nerve and washes it, which is why anesthesia of the entire upper jaw and covering it is obtained. soft tissues.

On turtles and corpses, we inserted needles and measuring probes of varying sizes into the foramen magnum palatine up to the foramen rotundum. The distances were not always the same: they ranged from 3.3 to 3.5 cm (we examined 40 skulls and corpses). To this approximately depth (a little more than 3 cm) “we began to insert the needle through the large palatine foramen

for anesthesia at a round hole. To do this, we took needles 5 cm long.

In the first years of anesthesia at the round foramen through the greater palatine foramen, then, along with other authors, considering the round foramen as the target point for anesthesia of the maxillary nerve, we, of course, tried to go deeper with the palatal route of this anesthesia to the round foramen.

We performed 242 conduction anesthesias of the maxillary nerve at the rotunda through the greater palatine foramen until January 1, 1927. In 230 cases, complete anesthesia of the entire upper jaw was observed, in 12 the effect was incomplete; in 14 (about 6%) the canal was impassable.

In 1927, we proposed to insert a needle into the palatine route, as with other routes of pterygopalatine anesthesia that we have improved, only to the pterygopalatine fossa, and not to the foramen rotundum.

Currently, we have experience in successfully performing pterygopalatine anesthesia via the palatal route in 1,478 cases.

Technique of pterygopalatine anesthesia via the palatal route. The patient opens his mouth wide. Find the injection site for anesthesia at the greater palatine foramen (the location of this point was discussed in detail above when describing the technique of palatal conduction anesthesia). Having smeared the found area with iodine, a syringe with a needle (or a 5 cm long needle without a syringe) is injected into it (see Fig. 97). Having given the needle direction from the front and bottom to back and up, we plunge it into the soft tissues of the palate; in this case, the needle falls either directly into the greater palatine foramen (Fig. 127), or onto the bone near the said foramen. If the needle is not in the hole, but on the bone near it, we release a little anesthetic solution and carefully slide the anesthetized area of the bone back and forth, medially and laterally, until the needle hits the greater palatine foramen, and move the needle through it further into the wing - palatal canal to a depth of 2.5-3 cm (Fig. 128). When the needle passes through the pterygopalatine canal, a weak resistance of the bone walls is felt, by which we judge that the needle is in the canal. Having made sure, one way or another, that we are outside the vessels (the leakage of drops of blood through the outer end of the needle or the appearance of blood in the syringe when the piston is pulled forward, towards itself, indicates that the needle has entered the vessel and, therefore, the need to slightly extend the needle and push it again with continuous release of anesthetic solution), release 1.5-2 ml of anesthetic solution.

After 10-15 minutes, anesthesia occurs in all areas innervated by the maxillary nerve.

The branches of the maxillary nerve, which together innervate the entire upper jaw (posterior superior alveolar nerves, infraorbital nerve and palatine nerves), begin in the pterygopalatine fossa.

Consequently, when an anesthetic solution is injected into the pterygopalatine fossa, all these branches are washed with the solution and anesthetized. Thus, without advancing the needle to the round hole, but by injecting it and the anesthetic solution only into the pterygopalatine fossa, the entire upper jaw is anesthetized.

Not very deep advancement of the injection needle into the pterygopalatine canal is always the best prevention against serious complications possible as a result of deep penetration.

movement of the injection needle into the pterygopalatine canal during the palatal (palatal) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia (breakage of the needle from the stop in the upper bony protrusion, penetration of the needle through the lower orbital fissure into the orbit and possible injury to the eyeball or even the optic nerve).

Of course, there is no need to use the palatal route of pterygopalatine anesthesia especially widely (for example, to remove one tooth). But with more or less significant intervention on the upper jaw, it is indicated.

Only in cases where there are obstacles to performing peripheral conduction anesthesia and anesthesia of the dental plexus due to damage to the perimaxillary soft tissues by a pronounced purulent-inflammatory process in the place where these anesthesia is performed, and in the absence of damage to the mucous membrane of the palate by this process, can pterygopalatine anesthesia be used through the palatal route and to remove one tooth that caused odontogenic osteomyelitis of the upper jaw.

It must be remembered that it is not always possible to use the palatal route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. As mentioned above, in 6% of cases, the pterygopalatine canal, according to our research, is impassable. Often, phenomena such as trismus, contracture of the lower jaw and localization of a painful lesion on the palate in the area of the injection site interfere with the use of the palatal route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. It should also be borne in mind that in some diseases of the dental system, the microflora of the oral cavity is very abundant and virulent, and in these cases, intraoral conduction anesthetic injections, especially central ones, are not entirely safe and should, whenever possible, be replaced with extraoral ones.

In connection with the above, we often have to use

extraoral pterygopalatine anesthesia.

In 1929, we improved the extraoral tubercular (tuberal) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia, previously known as “subzygomatic anesthesia.”

In 1930, we improved the orbital (orbital) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia.

In 1941, we developed a new subzygomatic-pterygoid route of pterygopalatine anesthesia.

In 1955, we improved the suprazygomatic route of pterygopalatine anesthesia.

Since 1929, the number of extraoral anesthetic injections at the round opening (extraoral pterygopalatine anesthesia) begins to increase significantly in our country due to a decrease in the number of such anesthetic injections through the palatal route (see table at the end

books).

Tubercular (tuberal) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. The path running along the tubercle of the posterior surface of the upper jaw and through the pterygopalatine fossa to the foramen rotundum was first proposed in 1900 by Matas and described in detail by Brown in 1909.

The Matas-Brown technique, which requires bringing the needle to the foramen rotundum, is fraught with serious complications, first of all, the possibility of the end of the needle entering the superior orbital fissure and damaging the cavernous sinus, or getting close to the optic foramen and damaging the optic nerve.

The tuberal route of pterygopalatine anesthesia according to the method we propose, which begins in exactly the same way as the extraoral tubercular (tuberal) conduction anesthesia that we developed (see above), and which we called tubercular (tuberal), is free from these serious complications, primarily because with it, the needle is directed not to the round hole, but only to the pterygopalatine fossa.

When performing extraoral pterygopalatine anesthesia via the tuberal route, turn the patient’s head to the left on the right, and

when operating on the left, turn the patient's head to the right. We palpate the surgical field on both the right and left sides with our left hand and, therefore, always perform the anesthetic injection with our right hand (see Fig. 83 and 84).

We first advance the needle, as for extraoral tubercular conduction anesthesia, in the direction from front to back, from bottom to top, from outside to inside, all the time in close contact with the posterior surface of the upper jaw. We first bring the needle to the maxillary tubercle. Then, in order to be able to safely advance the needle further, to the site of the target point of pterygopalatine anesthesia - the pterygopalatine fossa - when further advancing the needle, do not lose contact with the bone and do not fall with the end of the needle or /| i|jBfir ^L^^ ^ too low (may not ^* ^^^С»^^^\ | anesthesia occur), nor /^^^stj ^^^^1 ^ 1 too high (may 1

/bT^/ '•^^Bh ) ' \ to determine the hit of the che-

/»'^i, \\

y^ ^^^^vХ^-_^^-p res medial segment \/»it^^R*» .

^»»^ea-sS?'»'^' l inferior orbital fissure in \П^^' «rfetiS^I^^^^^^S' orbit and through the main- '< ' J ^^^^^И^ ^ ^/g

palatine opening in the nasal cavity), we are here, ®@1/^ Ф' ///»»i ^wlik- C at the maxillary tubercle, J^f

/f » l // ^'JJt^^tS we move the syringe significantly /^^^^^^3^^'^ but back. With this position, the needle and

during further Fig. 129. Tubercular (tuberal) path of advancement from the tubercle and pterygopalatine anesthesia.

GLUIZHR hp fivnpT ptuplmt The end of the needle after moving it along the back-inywtt.e not^ oude! WALK ^g the surface of the upper jaw (tubercle of the upper jaw)

FROM THE BONE WALL. Further, “her jaw) falls into the pterygopalatine fossa.

we try to get through the falciform fissure into the pterygopalatine fossa (Fig. 129). As stated earlier, we do not need to hit the foramen rotundum or necessarily the maxillary nerve with this anesthesia; Based on the analysis we made above, it is necessary to get the end of the needle only into the pterygopalatine fossa and fill it with an anesthetic solution.

In order to be able to sufficiently pull the syringe back when the end of the needle is in the area of the maxillary tubercle, without encountering obstacles from the external soft tissues, before starting the injection, we move the fold of the cheek forward, medial to the zygomatic-alveolar ridge.

To avoid too low or too high a direction of the needle and more or less accurately determine the middle height of the falciform fissure of the pterygopalatine fossa (the location of the target point and in the case of the extraoral tubercular path of pterygopalatine anesthesia), we propose to navigate by identifying through the soft

18 674 273

tissue with the thumb and forefinger of the left hand, the height of the zygomatic bone between its lower angle and the orbital edge.

To do this, before advancing the needle from the maxillary tubercle to the target point, when injecting from the right side, we move the index finger (lying at the beginning of the needle advance on the anterior surface of the ridge) to the lateral half of the lower orbital margin. and leave the thumb on the lower zygomatic corner. When injecting on the left side, we move the thumb to the lateral half of the lower orbital margin, and leave the index finger at the named angle and in this way determine the height of the zygomatic bone between these points. In this case, the upper border indicates the level of the foramen rotundum and the internal (medial) segment of the infraorbital fissure, and the lower border indicates the lower end of the pterygopalatine fossa.

For successful and safe implementation of the disassembled method of pterygopalatine anesthesia, it is necessary that the sharp end of the needle at the target point of this anesthesia is in the projection of the middle height of the zygomatic bone, but in no case higher than the upper and not lower than the lower point

Orbital (orbital) route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. In cases where it is impossible to use either the palatal or the mountainous route of pterygopalatine anesthesia, they resort to the orbital route.

Old authors (Voino-Yasenetsky, Hertel, Härtel, Payr, Raug, and Chevrier, Chevrier) considered it necessary to insert the end of the needle into the round hole during the orbital route of anesthesia of the maxillary nerve. In this case, Hertel and other authors inserted the needle into the orbit along its lower wall, and Voino-Yasenetsky proposed (1909) to insert it along the outer wall of the orbit, considering this path less dangerous and more accessible for the end of the needle to enter the round hole.

We recommend administering this numbing injection as follows:

Use the index finger of your left hand to feel the lower orbital edge of the orbit and with the same finger fix the injection site, which should be several millimeters medial to the middle of the lower orbital edge. The indicated finger is thus placed on the outer part of the lower orbital edge on the right, and on its inner part on the left (Fig. 130, 131).

When operating, a syringe with a needle 5-6 cm long is taken from both the right and left with the right hand.

First, the skin is pierced over the bony area of the anterior surface of the lower orbital margin. which is fixed with the index finger of the left hand and immediately before the injection is released by moving the finger to the side. When the needle hits the bone - the anterior surface of the lower orbital edge - a little anesthetic solution is released to anesthetize and moisturize the indicated area. Then

the end of the needle is moved upward, passed through the lower orbital edge and then advanced into the depths of the orbit. In this case, be sure to lift the syringe up and force the needle to slide along the bone. When moving the needle to the lower wall of the orbit, especially when moving it deeper along this wall, strictly monitor the close contact of the end of the needle with the bone and throughout the entire time of advancing the needle, release an anesthetic solution in small portions, as a result of which the eyeball, as well as the nerves, move upward and blood vessels of the eye. Igloo

advance along the moistened lower wall into the depths of the orbit by 3-3.5 cm and release the final portion (2-3 ml) of the anesthetic solution (see Fig. 130-131).

In total, 5 ml of anesthetic solution—5 ml of 2% novocaine + + 1 drop of adrenaline (1: 1000) (see footnote on page 314) is spent on pterygopalatine anesthesia with orbital pu-gem.

The indication for the production of pterygopalatine anesthesia by the orbital route is surgery for malignant neoplasms of the upper jaw, localized in the palatal and posterior areas of the upper jaw. Using the described technique, you can achieve good pain relief and avoid complications. The swelling of the lower eyelid that appears immediately after the anesthetic injection usually disappears quickly.

It is believed that with pterygopalatine anesthesia through the orbital route the following complications are possible: injury to the eyeball, vessels and nerves that supply and innervate the eyes, hemorrhage into the orbit and resulting blindness, probably due to injury to a large vein participating in the blood circulation of the optic nerve, injury to the optic nerve itself. optic nerve, penetration through the superior orbital fissure into the cavernous sinus and, finally,

1U' 275

spreading infection into the orbit, which is dangerous for the eye and is fraught with even more serious consequences due to the wide communication of the orbit with the base of the skull and cranium.

To avoid these complications, you must adhere to the following rules.

First of all, during pterygopalatine anesthesia through the orbital route, as when performing conduction anesthesia in general and central and basal anesthesia in particular, the strictest asepsis should be observed. Of course, with scrupulous aseptic injection, the risk of infection in the orbit disappears.

Further, with pterygopalatine anesthesia, as mentioned above, the anesthetic solution should be applied only to the pterygopalatine fossa and there is no need to go deeper during the orbital path of this anesthesia to the round hole. To do this, it is enough to insert the needle into the orbit only 3-3.5 cm, thereby eliminating the possibility of injury to the optic nerve and penetration into the superior orbital fissure. Released under a certain pressure at a specified depth, the anesthetic solution itself reaches the medial part of the lower orbital fissure and from there enters the pterygopalatine fossa.

To prevent and completely eliminate the possibility of injury to the eyeball, as well as the nerves and vessels that innervate and supply the eye, it is recommended to strictly adhere to the lower wall along the entire path of the needle into the depths of the orbit, continuously releasing an anesthetic solution in small portions.

It should also be added that pterygopalatine anesthesia by the orbital route also anesthetizes the orbital wall of the upper jaw, which, being innervated not only by the maxillary nerve, but also by the orbital one, has little anesthesia with all other routes of pterygopalatine anesthesia. With the right technique

this path is valuable and completely safe. You just need to stay close to the orbital plate of the upper jaw, do not go too deep and do not cross the lower orbital fissure (it is better not to reach it); finally, the entire path, as we said, needs to be slightly moistened with an anesthetic solution and a certain amount of anesthetic solution (2-3 ml) released at the end of the injection.

The orbital route of pterygopalatine anesthesia must be mastered. We need to be able to carry out this method well and correctly, because it often helps us out during operations for common inflammatory diseases.

processes and especially regarding malignant neoplasms of the upper jaw. These diseases most often begin on the alveolar process; usually the pathological process first of all involves the closest palatal and posterior areas of the upper jaw with the soft tissues covering them, and much later and less often - the upper, orbital, wall of the upper jaw.

Subzygomatic-pterygoid pathway of pterygopalatine anesthesia. In 1941, we proposed and developed a new way of pterygopalatine anesthesia. Due to the fact that this path begins at the lower edge of the zygomatic arch, from where the needle is first directed to the pterygoid process, and then to the target point of pterygopalatine anesthesia - the pterygopalatine fossa - we called it the subzygomatic-pterygoid path.

The fact is that on the same sagittal line with the outer plate of the pterygoid process there is also an oval opening.

stye and pterygopalatine fossa. The foramen ovale is located behind the pterygoid process, and the pterygopalatine fossa is located in front.

Therefore, in order to accurately enter the pterygopalatine fossa by the subzygomatic route, you can, with the same success, as with anesthesia at the oval foramen (see anesthesia at the oval foramen), use a preliminary direction of the needle to the outer plate of the pterygoid process, and then to the detected depth advance the needle towards the pterygopalatine fossa and enter it.

To accurately target the pterygoid process, we orient ourselves using our proposed identification trago-orbital (tragus-orbital) line. For successful anesthesia at the foramen ovale, we use the subzygomatic route. an identification line was found and proposed, drawn from the tragus of the ear to the outer edge of the orbit and named in connection with this the tragus-orbital (trago-orbital) (Fig. 132). The middle of this line is always located in the projection of the outer plate of the pterygoid process.

Technique of pterygopalatine anesthesia via the subzygomatic-pterygoid route. We begin the injection in the middle of the trago-orbital line at the lower edge of the zygomatic arch (Fig. 133). First, we bring the end of the needle to the outer plate of the pterygoid process, mark the depth of this point on the needle and fix the established depth with the end of the middle finger of the right hand conducting the injection.

Then we extend the needle a little more than half outward and again plunge it deeper into the original distance - to the place fixed on the needle with the end of the indicated finger. In this case, to obtain pterygopalatine anesthesia in this way, we move the needle again with an inclination forward, get into the pterygopalatine fossa (Fig. 134 and 135) and fill it with an anesthetic solution.

The subzygomatic-pterygoid route of pterygopalatine anesthesia is of great importance, since the injection site is relatively far from the affected upper jaw and painful foci of adjacent soft tissues.

Suprazygomatic route of pterygopalatine anesthesia. The suprazygomatic route of pterygopalatine anesthesia (anesthesia at the round opening) according to Payru, in which the injection site is located at the upper corner of the zygomatic bone, between its horizontal and vertical edges, is not accurate. Then, due to the direction of the needle along this path in the projection of the sphenopalatine foramen, the needle can easily penetrate the nasal cavity and introduce infection into the base of the skull. Our technique of pterygopalatine anesthesia via the suprazygomatic route is outlined below in the section “Suprazygomatic, so-called temporal pathways of conduction anesthesia of the maxillary and mandibular nerves” (see p. 319).

The existence of several routes makes it possible to carry out pterygopalatine anesthesia even when there are obstacles to the use of one or another of them,

In case of non-opening of the mouth (trismus, contracture, ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint), when the palatal route of this anesthesia is not applicable, you can use the tuberosity, subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic routes. If the tubercular part of the upper jaw and adjacent soft tissues are affected, you can use either the palatal route (if the opening of the mouth and the patency of the pterygopalatine canal allow this), or the subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic pathways (if the mouth is not opened^. In case of damage to the area of the maxillary tubercle and the zygomatic arch can be used with sufficient opening of the mouth through the palatal way. With common malignant neoplasms of the upper jaw, the blastomatous process can involve the tubercular and palatal parts. The soft tissues adjacent to the posterior wall of the upper jaw in these cases can also be involved in the process. Common inflammatory processes of the maxillary areas, especially of traumatic origin, due to contracture of the lower jaw, osteomyelitis of the upper jaw, zygomatic bone, zygomatic arch and ramus of the lower jaw, exclude the use of the palatine, tuberosity, subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic tracts.In such cases, we perform pterygopalatine anesthesia through the orbital route.

You can judge the success of the pterygopalatine anesthesia, as with all conduction anesthesia of the maxillofacial

274

area, by the appearance of anesthesia or paresthesia of areas of facial skin in the area innervated by the peripheral branches of the anesthetized nerve. In this case, with conductive anesthesia of the maxillary nerve through the palatine, tubercular, subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic pathways, an indicator of the success of anesthesia is numbness of the areas of the upper lip, wing of the nose and lower eyelid of the corresponding side. However, this sign is not indicative of pterygopalatine anesthesia performed through the orbital route. For in the first cases, the appearance of anesthesia in areas innervated by the peripheral branches of the infraorbital nerve indicates that the solution in the pterygopalatine fossa has washed away the maxillary nerve and the initial segments of its main branches (infraorbital, posterior superior alveolar and palatine);

in the latter case, anesthesia of the indicated peripheral areas can occur as a result of washing off the infraorbital nerve with the solution while moving the needle and solution along the lower wall of the orbit, even if it does not enter the pterygopalatine fossa through the lower orbital fissure. Therefore, a sign of the success of pterygopalatine anesthesia through the orbital route and the resulting anesthesia of the upper jaw and its teeth is the onset of anesthesia in the area of the mucous membrane of the palate of the corresponding side.

Complications 1. Infection. If the mouth is significantly infected, the use of the intraoral (palatal) route should be avoided and the extraoral routes of pterygopalatine anesthesia (tubercular, subzygomatic-pterygoid, suprazygomatic and orbital) should be used to avoid infection of the pterygopalatine fossa.

2. Entry of the needle into the nasal cavity. This complication occurs in the palatal route, when the injection is made too backward and the needle gets between the hard and soft palate into the nasal cavity. Signs of a needle entering the nasal cavity in this way are the following: the absence of a feeling of some resistance when moving the needle deeper and the anesthetic solution getting into the pharynx, which causes coughing movements in the patient. Naturally, in this case no anesthesia will occur and you need to make a new anesthetic injection into the pterygopalatine fossa via the palatal route. In itself, the entry of an anesthetic solution into the nasal cavity and from there into the pharynx does not pose any danger, but it can cause another very serious complication - needle breakage. If the anesthetic solution gets into the pharynx, it can force the patient to suddenly close his mouth, which can cause the needle to break. Of course, if the needle gets into the nasal cavity, it becomes infected and for a second injection, you should take another, sterile one. To avoid sudden closure of the mouth, especially in children, before this anesthetic injection, you can insert a rubber stopper or mouth dilator between the teeth of the opposite side to the patient,

A complication in the form of a needle entering the nasal cavity can also occur when performing pterygopalatine anesthesia through the tubercular route, when the end of the needle, if the depression is too large, enters the nose through the main palatine opening in the medial wall (vertical part of the palatine bone) of the pterygopalatine fossa . In this case, getting an injection needle into the nasal cavity leads to infection of the injection needle and the need to repeat anesthesia after replacing the needle with a sterile one and to infection at the base of the skull when the infected needle is pulled back out.

To prevent the needle from entering the nasal cavity during the tuberosity, one should strive to get the end of the needle into the middle of the height of the pterygopalatine fossa, below the main palatine opening, located in the upper part of the pterygopalatine fossa.

Accurate determination of the depth of the pterygopalatine fossa during the tubercular path of disassembled anesthesia by preliminary moving the injection needle below the subsequent direction shown, towards the lower segment of the pterygopalatine fossa, is the best prevention against getting into it. needles through the lower orbital fissure into the orbit, and against its entry through the sphenopalatine opening into the nasal cavity

3. Injury to blood vessels and nerves. Large vessels and nerves can be injured during pterygopalatine anesthesia via the tuberosity and especially the orbital route. The significance and prevention of this complication has already been discussed when analyzing these pathways and will be discussed in detail below in the corresponding chapter.

It should be repeated here that in order to avoid injury by the needle to the vessels and nerves in the pterygopalatine canal during the palatal route of pterygopalatine anesthesia, one must use a needle with a short beveled end and continuously release a little anesthetic solution during the entire time the needle is advanced into the depths of the pterygopalatine canal, and the anesthetic injection, especially here, should be carried out slowly.

4. Double vision. This complication is explained by temporary paralysis of some of the motor nerves of the eye due to contact with an anesthetic solution. Double vision occurs: with the orbital path almost always, with the palatine - in cases of too deep advancement of the needle, with the tuberosity, subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic - in cases where the end of the needle gets into the upper segment of the pterygopalatine fossa and, as a result, leakage of the solution through the lower orbital fissure into orbit.

Double vision associated with pterygopalatine anesthesia goes away after half an hour, but sometimes lasts up to 2 hours. It is recommended to warn patients about the possibility of such a complication.

5. Breakage of the needle The needle can break due to pushing it too deep along the palatal path and sharply pressing the tip of the needle into the base of the skull - the upper wall of the pterygopalatine

fossa, and in the case of the subzygomatic-pterygoid and suprazygomatic tracts - from the needle resting on the outer wall of the pterygoid process. The needle can break if it is sharply pressed against the inner wall of the pterygopalatine fossa when carrying out this anesthesia by the tuberous route.

For pterygopalatine anesthesia it is necessary to use good quality needles. The needle thickness should be 0.5-0.8 mm. Very good needles made of high-quality stainless steel, which can be thinner

How is torsal anesthesia performed?

Weisbrem anesthesia requires precise insertion of a needle at a specific point. The dentist must reach the mandibular eminence, which is located on the outer part of the jaw close to the bony uvula. There is a lot of fiber in this place, in which three nerves connect, which will be subjected to analgesia. Access to this area can be intra-oral or extra-oral, but the former is most often used.

To navigate inside the oral cavity and search for the necessary anatomical structures, the specialist acts by palpation or without it (apodactyl method). With the palpation technique, the dentist first finds the temporal ridge and the depression behind the large molars, which will serve as landmarks. When anesthetizing the right half of the jaw, the specialist palpates the indicated formations with the index finger of the left hand, and if it is necessary to numb the left half, he acts with the first finger of the same hand.

The apodactylic technique does not involve probing with fingers. The dentist is guided visually by known formations, the main one of which will be the pterygomandibular fold, located medially from the temporal crest.

When performing torusal anesthesia, the dentist observes a number of conditions that ensure safe delivery of the anesthetic and an adequate level of pain relief:

- The patient should open his mouth as wide as possible;

- When puncturing with a needle, you should orient yourself along the pterygomandibular fold, at the point between the upper and middle thirds of which, in the outer part of the mandibular ridge, an anesthetic is injected;

- If there are teeth on the upper jaw, then the point that is located half a centimeter downward from the lower surface of the last large molar can be taken as a reference point.

The technique of torsal intraoral anesthesia includes several successive stages:

- The dentist holds the syringe at the level of the second or 3rd molar, directing the needle to the mandibular branch at almost a right angle;

- When the needle has pierced the mucosa, it is moved until it reaches the bone surface - approximately 3 cm deep into the soft tissue;

- As the needle moves, an anesthetic drug is gradually introduced;

- Injection of 2 ml of an anesthetic to block the sensitivity of the buccal and inferior alveolar nerve trunks;

- To anesthetize the lingual nerve, the dentist moves the needle in the opposite direction about half a centimeter, after which another milliliter of anesthetic is injected into the tissue.

For torusal anesthesia, widely used anesthetics are used - novocaine, lidocaine, ultracaine forte . The patient feels the analgesic effect after 15-20 minutes. It can last up to an hour and a half, depending on what drug was chosen and for what purpose. For long-term dental procedures, longer-acting anesthetics are preferred.

Modern anesthetic drugs are quite strong, so the dose may be less. When using ultracaine, it is no more than 2 ml.

If the patient for some reason (injury, muscle contractures, for example) cannot open his mouth wide, he will be given extraoral torus anesthesia, which is carried out in a number of ways:

- The specialist determines the landmarks of the lower jaw on the surface of the skin, which is pre-treated with an antiseptic;

- The needle is inserted in the area of the base of the mandibular bone one and a half centimeters forward from its angle;

- Move the needle upward by 3-4 cm along the outer surface of the process of the lower jaw, while the dentist should feel the bone surface with the needle;

- Injection of anesthetic into the required area and withdrawal of the needle.

The anesthesia zone for torusal anesthesia includes:

- Mandibular teeth from the canine to the eighth on the side of anesthesia, it is possible that the incisors will also be exposed to the drug;

- Oral mucosa, bony surface of the lower jaw from the side of the cheek and tongue;

- Skin and mucous membrane of the cheek and lower lip;

- Part of the tongue from the side of anesthesia;

- Chin area.

In some cases, complete desensitization of the buccal nerve may not be achieved, which may leave molars and molars susceptible to pain. To eliminate this deficiency, the dentist must impregnate the transitional fold of the mucous membrane directly next to these teeth with an anesthetic.

The technique of performing torusal anesthesia is more complicated than with conventional mandibular anesthesia, and requires the experience and skill of a specialist, because the ultimate goal is to turn off three nerves at once, and for this you need to get strictly to a certain point. In addition, this type of pain relief can cause some complications.

Torusal anesthesia is accompanied by the same complications that are characteristic of mandibular anesthesia. Contractures of the mandibular muscles are possible when using a low-quality anesthetic, damage to muscle fibers, periosteum or bone tissue of the lower jaw. In case of vascular injury, hematomas can form in the soft tissues, and if the anesthetic drug enters the bloodstream, the patient will experience its general effect, including some toxic effects. Careless manipulations can lead to needle breakage. The described complications are usually associated with a violation of anesthesia technique and insufficient experience of the specialist.

PLEXUS CONDUCTION ANESTHESIA OF THE UPPER LIMB

Areas of anesthesia

Supraclavicular brachial plexus block.

A pillow is placed under the head and shoulder girdle, the head is turned in the opposite direction, the limb is located along the body. From a point located medial to the middle of the clavicle by 1 cm and above its upper edge by 1-1.5 cm, 1 rib is reached. Obtaining paresthesia is mandatory. Dose of 1-2% anesthetic - up to 50 ml.

Axillary brachial plexus block.

A tourniquet is applied to the abducted, supinated and bent limb at the elbow at the site of attachment of the pectoralis major muscle to the shoulder. The axillary artery is palpated at the apex of the axillary fossa above the head of the humerus. From this point, the needle is inserted until the fascial “click” occurs. Obtaining paresthesia is mandatory. Dose of 1-2% anesthetic up to 40 ml. The tourniquet is removed after 8 minutes.

Blockade of the long branches of the brachial plexus at the level of the wrist joint. median - on the supinated limb along the medial edge of the tubercle of the polygonal bone to a depth of 0.6-0.7 cm. Dose - 10-15ml of 1-2% anesthetic. ulna - on the supinated limb along the medial edge of the pisiform bone until paresthesia is obtained. Dose - 10-15ml of 1-2% anesthetic. radial - on the pronated limb at the base of the anatomical snuffbox, 10 ml of 1-2% anesthetic is used to create a transverse subcutaneous infiltrate 3-5 cm long.

INTRAOSSEAL ANESTHESIA - INDICATIONS, TECHNIQUES, COMPLICATIONS

Indications: for pain relief from operations on the upper and lower extremities, including bones. It is performed under a tourniquet, so the operation time should be limited to two hours. Technique: To anesthetize the upper limb, the olecranon process is usually punctured; for pain relief of the lower limb - the femoral condyle, although the metaphysis of any bone can be punctured. A tourniquet is applied to a highly raised limb for better blood flow above the site of the intended operation. At the site where the needle is inserted into the bony protrusion, the skin, subcutaneous tissue and periosteum are anesthetized with a 0.25% solution of novocaine through a thick needle. Then, with a rotational movement, a needle with a mandrel is inserted into the cancellous bone. The bone itself is anesthetized by injecting 20 ml of 5% novocaine (the solution must be freshly prepared!). This moment is extremely painful due to increased intraosseous pressure, so novocaine is administered very slowly. Wait 5-7 minutes, after which 0.5% novocaine is administered: for anesthesia of the upper limb - 60-80 ml; lower - 80-100 ml. Anesthesia occurs within 10-15 minutes. Before removing the tourniquet, 2 ml of caffeine sodium benzoate is injected subcutaneously to prevent the development of collapse due to the release of novocaine into the blood from the bone.

Complications are usually associated with rapid removal of the tourniquet and are manifested by paleness of the face, cold sweat, vascular insufficiency, pain in the area where the tourniquet is applied, and difficulty in hemostasis during surgery.

Novocaine blockades (indications, technique of cervical vagosympathetic, perinephric blockades)

Novocaine blockade is a method of nonspecific pathogenetic therapy based, on the one hand, on a temporary interruption of peripheral nerve conduction, and on the other, on the effect of non-concentrated solutions of novocaine on the regulatory functions of the central nervous system; gives a stable positive effect in inflammatory diseases and various types of muscle tone disorders - spasms are resolved and tone is restored; the physiological state of the vascular wall is restored. Perinephric novocaine blockade. Indications: acute intestinal obstruction, appendicular infiltrate, intestinal paresis of traumatic or postoperative origin, traumatic and burn shock, renal colic, acute cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, reflex anuria. Technique. The patient is placed on his healthy side with a cushion placed under the lumbar region. 1-5 ml of 0.25% novocaine solution is injected intradermally into the angle formed by the XII rib and the long back muscles. Then, through the formed nodule, into the depths of the soft tissues, strictly perpendicular to the surface of the skin, a long (10-12 cm) needle is advanced, mounted on a syringe with a solution of novocaine. Advancement of the needle is preconditioned by continuous injection of the solution. Having passed through the muscle layer and the posterior leaf (the posterior leaf of the renal fascia creates some resistance when the needle moves) of the renal fascia, the end of the needle enters the interfascial space (at a depth of 8-12 cm), as evidenced by the free injection of novocaine without any effort on the part of doctor and the absence of reverse flow of liquid from the needle when removing the syringe. If there is no reverse flow of the solution, inject 60-120 ml of a 0.25% novocaine solution. The novocaine solution spreads to the area where the renal and solar plexuses are located, reaching the splanchnic nerves.

Cervical vagosympathetic blockade . Indications: chest injury, conditions after operations on the chest organs to reduce pain and prevent reflex respiratory and circulatory disorders, bronchospasm, pleuropulmonary shock, hiccups after operations on the stomach, traumatic brain injury. Technique: the patient is placed on his back with a bolster under his shoulder blades. The head is thrown back and turned in the direction opposite to the blockade. The posterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is determined by palpation and a lemon peel is made approximately in its middle (immediately above or below the external jugular vein intersecting with it). Take a 20 ml syringe with a long needle, inject it at the same point and move the needle upward and medially towards the anterior surface of the vertebrae until it stops. Then the needle is moved back a little and 60 ml of a 0.25% novocaine solution is injected. If the blockade is carried out correctly, then on the side of the blockade the Claude Bernard-Horner symptom will appear: narrowing of the palpebral fissure, dilation of the pupil, ptosis of the upper eyelid.

55. Bleeding (haemorrhagia) is the flow (outflow) of blood from the lumen of a blood vessel due to its damage or disruption of the permeability of its wall.

All bleeding is distinguished by the type of damaged vessel and is divided into arterial, venous, capillary and parenchymal.

• Arterial bleeding. The blood flows out quickly, under pressure, often in a pulsating stream, and is bright scarlet in color. The rate of blood loss is quite high. The volume of blood loss depends on the caliber of the vessel and the nature of the injury (lateral, complete, etc.).

• Venous bleeding. Constant bleeding of cherry-colored blood.

• Capillary bleeding. Mixed bleeding caused by damage to capillaries, small arteries and veins.

• Parenchymal bleeding occurs due to damage to parenchymal organs: liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs. In essence, it is capillary bleeding, but is usually more dangerous, which is associated with the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the organs.

According to the mechanism of occurrence

Depending on the cause, there are three types of bleeding:

• Haemorrhagia per rhexin - bleeding due to mechanical

• Haemorrhagia per diabrosin - bleeding due to arrosion (

• Haemorrhagia per diapedesin - bleeding when the permeability of the vascular wall is disrupted at the microscopic level.

Depending on the time of occurrence, bleeding can be primary or secondary.

The occurrence of primary bleeding is associated with direct damage to the vessel during injury. It appears immediately or in the first hours after damage.

Secondary bleeding can be early (usually from several hours to 4-5 days after injury) and late (more than 4-5 days after injury).

With the flow

All bleeding can be acute or chronic. In acute bleeding, bleeding occurs in a short period of time, and in chronic bleeding, it occurs gradually, in small portions, sometimes a slight, periodic bleeding is observed for many days. Chronic bleeding can occur with stomach and duodenal ulcers, malignant tumors, hemorrhoids, uterine fibroids, etc.

There are different classifications of the severity of blood loss. It is convenient to distinguish four degrees of severity of blood loss:

• mild degree - loss of up to 10% of bcc (up to 500 ml);

• moderate degree - loss of 10-20% of bcc (500-1000 ml);

• severe degree - loss of 21-30% of bcc (1000-1500 ml);

• massive blood loss - loss of more than 30% of the blood volume (more than 1500 ml). Determining the severity of blood loss is extremely important for deciding on the choice of treatment tactics.

87. Closed chest injury, types of pneumothorax, clinic, first aid.

Closed chest injury - damage to the rib cage and chest organs while maintaining the integrity of the integumentary tissues. The mechanisms of causing these injuries can be single or multiple blows with blunt objects and surfaces during road accidents, falls from a height, beatings, as well as sudden one-time or multiple short-term or long-term compression of the victim in rubble or in a crowd of people.

Complications of closed blunt chest trauma include acute respiratory, cardiac and cardiopulmonary failure as a result of rib fractures, bruises and ruptures of lung tissue, cardiac injury and traumatic asphyxia.

Pneumothorax is a pathological condition characterized by the presence of air in the pleural cavity (the cavity formed by the layers of the pleura - the outer lining of the lungs).

Types of pneumothorax:

- Closed pneumothorax - develops in cases where air enters the pleural cavity through a pleural defect, but the defect is small and quickly closes. There is no communication between the pleural cavity and the environment, and the volume of air entering the pleural cavity does not increase. Clinically, it has the mildest course: a small amount of air can resolve on its own.

- Open pneumothorax is an accumulation of air in the pleural cavity that communicates with the environment through a wound in the chest wall or through a damaged large bronchus. When you inhale, air enters the pleural cavity, and when you exhale, it comes out back. The pressure in the pleural cavity becomes equal to atmospheric pressure, which leads to the collapse of the lung and its exclusion from breathing.

- Valvular (tension) pneumothorax is the most severe option. If the wound is large and a medium-sized bronchus is damaged, a valve structure is formed that allows air into the pleural cavity at the time of inhalation and prevents it from escaping into the environment during exhalation, while the volume of air in the pleural cavity gradually increases. This leads to displacement and compression of the mediastinal organs (heart, large vessels) with significant respiratory and circulatory disorders.

Clinic:

- chest pain that gets worse with breathing, usually when inhaling;

- shallow breathing, a symptom of “broken breath”;

- tachypnea more than 18 respiratory movements per minute;

— pain with sagittal and frontal loads on the rib frame;

- chest deformation, flotation with bilateral rib fractures;

- cyanosis, increased blood pressure, tachycardia;

- boxed percussion sound (pneumothorax) or dullness of percussion sound (hemothorax) on the injured side:

— there is also a weakening (absence) of respiratory sounds during auscultation;

- subcutaneous emphysema (creating increasing volume of the neck, face, spreading to the chest);

- swelling and swelling of the neck veins;

- cyanosis of the upper half of the body;

- multiple small hemorrhages on the face, neck, upper limbs;

- drop in blood pressure, clinical and biological death.

First aid:

- analgin 50% solution 2 - 4 ml intravenously (intramuscular) or promedol 2% solution 2 ml intramuscularly;

— inhalation anesthesia with nitrous oxide and oxygen in a ratio of 1: 2;

— oxygen therapy;

— immobilizing bandage or adhesive plaster circular bandage for visible deformation of the rib frame;

- with valvular pneumothorax (progressive deterioration of the condition, increasing shortness of breath, shift of the mediastinum to the healthy side) - puncture of the pleural cavity in the second (third) intercostal space in order to convert a tension pneumothorax into an open one:

— cardiac medications according to indications;

- antishock therapy according to indications.

Complications of conduction anesthesia

Complications of conduction anesthesia are rarely recorded with careful adherence to pain management techniques, calculation of drug doses, and determination of indications for the method. The most serious consequence of anesthesia is considered to be neuropathy, and an extremely dangerous complication is an allergy or individual reaction to anesthetics.

Allergies can manifest as anaphylactic shock with severe hypotension, loss of consciousness, respiratory and cardiac disorders. If an anesthetic is introduced into the bloodstream if the manipulation technique is not followed, a systemic reaction will develop - cardiac arrhythmia, fainting, collapse.

Neuropathy is a consequence of disruption of the integrity of the nerve during anesthesia. It is manifested by sensitivity disorders, numbness, soreness or muscle weakness in the innervation zone. This complication occurs in less than 1% of cases, and therefore should not be a reason to refuse regional anesthesia.

Other possible complications include injuries to large vessels, pneumothorax, infection of the anesthetic injection site, toxic effects from drugs (primarily hypotension), damage to the lung or other internal organ.

The technique of blocking individual nerves or plexuses is extremely important in a variety of areas of surgery, including maxillofacial surgery. The method is safe, highly effective, and allows for complex and fairly lengthy interventions with minimal risk to the patient.

Essential safety conditions are careful adherence to technique, experience and high qualifications of the anesthesiologist. Carrying out operations under general anesthesia can reduce not only the number of complications, but also the duration of subsequent rehabilitation, making the postoperative period easier.